The last couple of evenings I’ve been reading a small volume produced in 1965 by the Sussex Record Society. It’s by Richard F Dell and titled Rye Port Books; it documents shipping in and out of Rye in East Sussex between 1566 and 1590, ie. a large part of the reign of Elizabeth I. Rye, at this date, had a large harbour which irrevocably silted up around 1600.

While this might sound somewhat dull, they were interesting times (to say the least) when there was essentially a “cold war” between Protestant England and Catholic Europe. Understandably no-one was permitted to leave (or enter) the country without government permission, although many did and not a few were either Catholics fleeing to France or Italy or they were spies for one side or the other (or indeed both).

Rye at that time was one of the major ports for both passengers and freight between England and France and the Low Countries. Regrettably there is little detail of people movements in these records, apart from the occasional note of a boat carrying “20 passengers”. This is a shame because even at this date there were immigration officers stationed at every port such as Rye. Their job, as today, was to interrogate and determine the bona fides of all travellers and naturally to detain any they thought might be Catholic insurgents or spies. From reading elsewhere about the spy rings of Elizabethan England (masterminded by Lord Burghley and Sir Francis Walsingham) it is clear there was also a large amount of mail travelling back and forth, mostly being hand-carried by couriers. [For more on this see Stephen Alford, The Watchers: A Secret History of the Reign of Elizabeth I. Review when I’ve finished reading it.]

This book is more about the trade which was happening. Although there are several vessels logged which seem to do nothing but ply back and forth between Rye and Dieppe (the preferred route to France) carrying what today would be called “stuff”, there is also a large amount of goods travelling round the coast of the country, especially between Rye and London, but also as far afield as Newcastle, Spain and Portugal. Remember these are times when the roads were poor, if they existed at all, and a journey from Rye to London by cart carrying goods would take a week or more whereas in good weather a boat could sail between Rye and London in a couple of days. None of the ships involved are of any size; the largest I saw mentioned was 70 tons and they go down to tiny boats of 10 tons; the average is probably around 25-30 tons. These really are tiny boats; the

Mary Rose by contrast was rated at 500 tons.

A large section of the book is a line by line summary of every ship which enters or departs Rye over this 35 year period (give or take a few gaps), all constructed from the surviving Elizabethan records in the Sussex County Archive, the National Archives and the Rye Town Records.

Most of the cargo was quite mundane, and perhaps what one might expect: grain of various sorts, wood (ship upon ship full of wood), coal, wool, cloth of various types, wine; and there were many loads which are just recorded as “mixed” so who knows what they contained. Iron appears fairly regularly, and in significant quantities too (the Sussex Downs were an iron smelting centre at this date) and there are several shipments of ordnance including the occasional iron cannon.

But there are some surprising (at least to me) things, such as: lupins, vinegar, apples (from France), oranges and lemons (yes even so; they come in from Spain and Portugal), hops (being traded in both directions), horses (strangely mostly out-bound), cony skins, wolf skins, bricks (being imported from the Low Countries; a single 40 ton ship can carry at least 10,000). And it goes on with nuts, spices, lead, paper, hosiery, cochineal, woad (presumably for use as a dyestuff), herrings (red and white), codfish, quails and scrap brass. Another ship brings in “6 asses”. All of this is, of course, taxed.

But there were several entries which really caught my eye. One cargo is documented as “Mixed inc. tennys bawles”; another contains “French playing cards”. Then there’s a mixed shipment which includes hawks (“6 Tassell hawks, 7 Falcon hawks, 3 Martin hawks, imported by Walter Libon, alien”). Lastlly, there are several shipments of old shoes to London! One can only guess that scrap leather had a value, but for what?

We think we live in interesting times, ship strange goods around in containers, using humongous amounts of oil. But all this was being done by the power of man, horse, tide and wind.

Who said history is dull!

The idea is good and the book should have been interesting, but I found it facile and superficial: like cheap brawn, lots of aspic with very little meat. I had to give up on it half way through.

The idea is good and the book should have been interesting, but I found it facile and superficial: like cheap brawn, lots of aspic with very little meat. I had to give up on it half way through.

What emerges is a “who nearly done it” from the misty and murky world of Elizabethan espionage. Espionage that, in those dangerously unsettled times, was essential for the survival of Protestant England and Elizabeth. Espionage, which was perhaps the first really consolidated use by the state, and whose methods very much laid the foundations even for today’s shadowy world of subterfuge.

What emerges is a “who nearly done it” from the misty and murky world of Elizabethan espionage. Espionage that, in those dangerously unsettled times, was essential for the survival of Protestant England and Elizabeth. Espionage, which was perhaps the first really consolidated use by the state, and whose methods very much laid the foundations even for today’s shadowy world of subterfuge.

This is, in the words of the Preface, “a book that invites the reader on a journey from map to map, to let their imagination run free”. It is a curious collection of historical maps, around which the author tells the stories the places and voyages which gave birth to the maps.

This is, in the words of the Preface, “a book that invites the reader on a journey from map to map, to let their imagination run free”. It is a curious collection of historical maps, around which the author tells the stories the places and voyages which gave birth to the maps. Čapek (1890-1938) was a Czech novelist, dramatist and journalist who was mostly active in the 1920s and 30s. He is possibly best known today for two plays written with his brother Josef: R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots) and Pictures from the Insects’ Life (aka. The Insect Play). This latter I have known since school as we did it as the school play in my final year; it is strange, weird and disturbing. With R.U.R. Čapek is credited with the invention of the term “robot”.

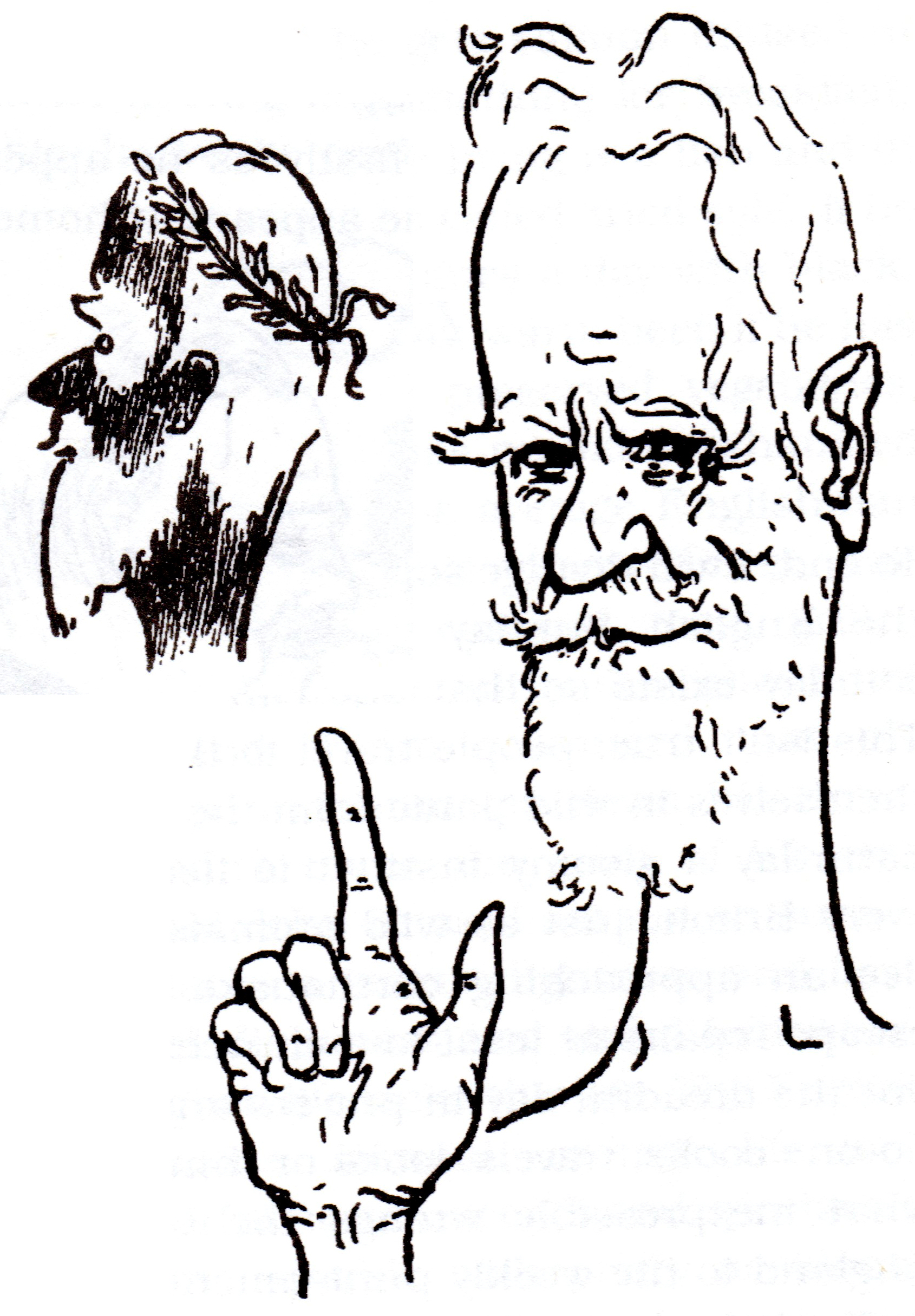

Čapek (1890-1938) was a Czech novelist, dramatist and journalist who was mostly active in the 1920s and 30s. He is possibly best known today for two plays written with his brother Josef: R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots) and Pictures from the Insects’ Life (aka. The Insect Play). This latter I have known since school as we did it as the school play in my final year; it is strange, weird and disturbing. With R.U.R. Čapek is credited with the invention of the term “robot”. This is an almost supernatural personality, Mr Bernard Shaw. I couldn’t draw him better because he is always moving and talking. He is immensely tall, thin and straight and looks half like God and half like a very malicious satyr, who, however, by a thousand-year process of sublimation has lost everything that is too natural. He has white hair, a white beard and very pink skin, inhumanly clear eyes, a strong and pugnacious nose, something knightly from Don

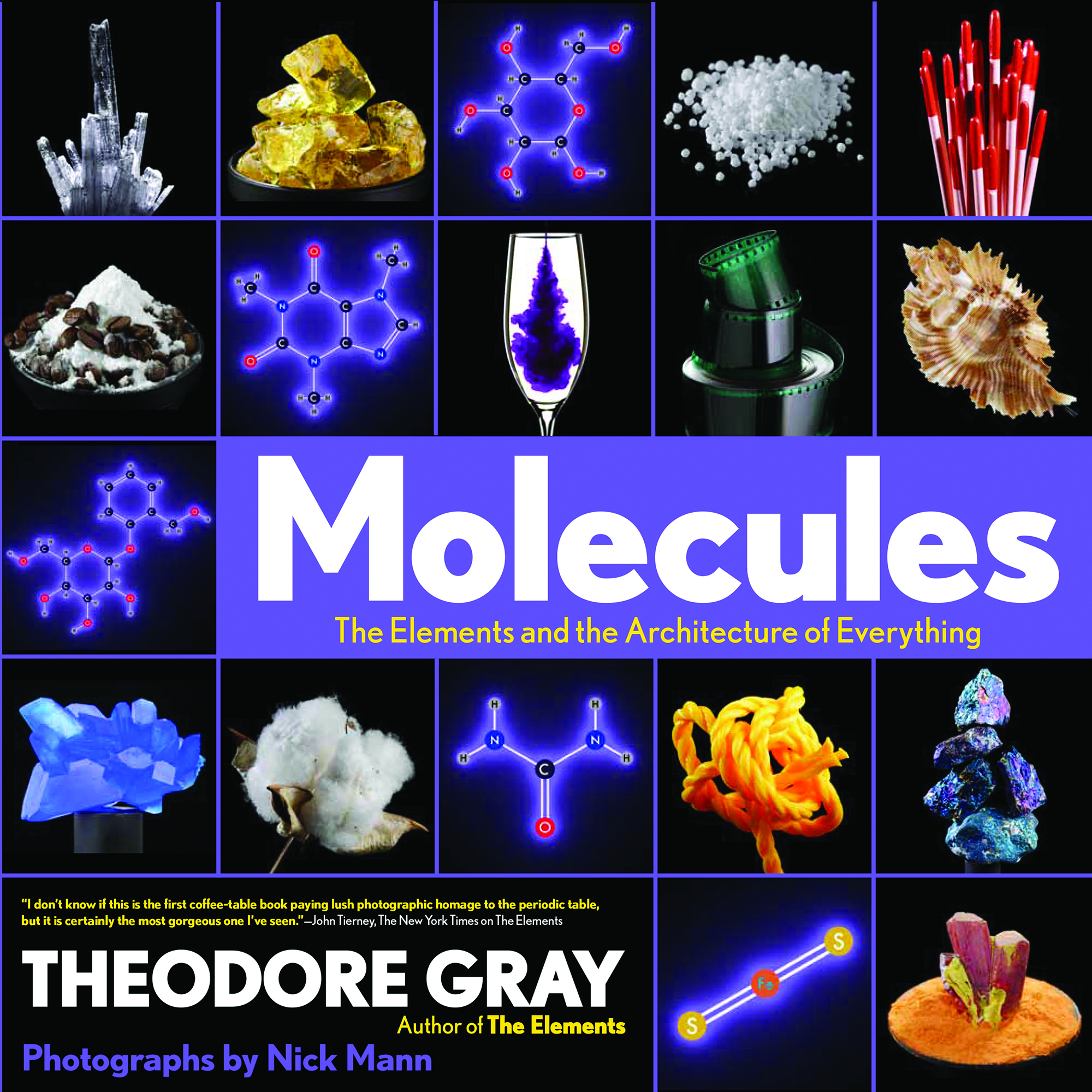

This is an almost supernatural personality, Mr Bernard Shaw. I couldn’t draw him better because he is always moving and talking. He is immensely tall, thin and straight and looks half like God and half like a very malicious satyr, who, however, by a thousand-year process of sublimation has lost everything that is too natural. He has white hair, a white beard and very pink skin, inhumanly clear eyes, a strong and pugnacious nose, something knightly from Don This is another of my Christmas acquisitions. It is a large coffee table book of almost 250 pages containing (mostly) photographs and diagrams on a black background with relatively little, but simple, textual explanation. It is a science book for the non- or only-just-scientist in which Gray sets out to show us how everything around us is built.

This is another of my Christmas acquisitions. It is a large coffee table book of almost 250 pages containing (mostly) photographs and diagrams on a black background with relatively little, but simple, textual explanation. It is a science book for the non- or only-just-scientist in which Gray sets out to show us how everything around us is built.

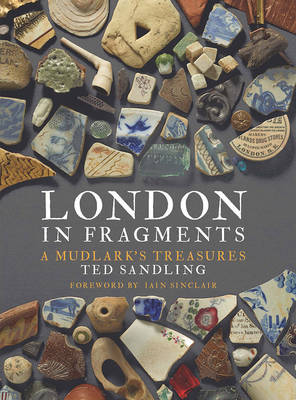

I was given this book at Christmas – well what else do you give a Londoner who is interested in the history and eccentricity of the city? I’ve been reading it in small chunks, which is why I’ve only just finished it.

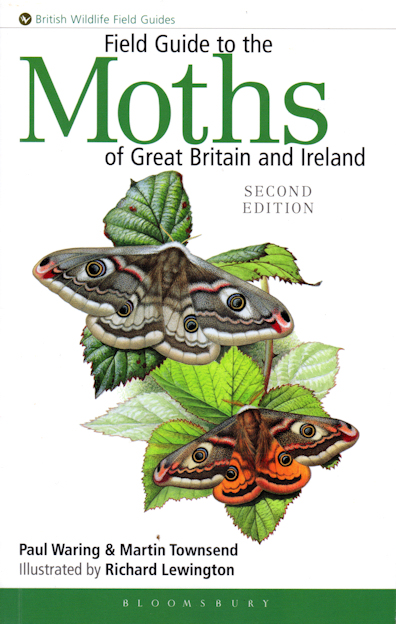

I was given this book at Christmas – well what else do you give a Londoner who is interested in the history and eccentricity of the city? I’ve been reading it in small chunks, which is why I’ve only just finished it. This is a magnificent tome, but not what I would define as a “field guide”: for an octavo paperback of almost 450 pages, on glossy paper and weighing almost 900 gm you would need a poacher’s pocket or a JCB to carry it around. It is a reference book — and a brilliant one at that — but as such it is not something to be read from cover to cover but explored when needed. It is an essential on the shelves of anyone with an interest in the huge diversity of the insect world, especially, obviously, moths.

This is a magnificent tome, but not what I would define as a “field guide”: for an octavo paperback of almost 450 pages, on glossy paper and weighing almost 900 gm you would need a poacher’s pocket or a JCB to carry it around. It is a reference book — and a brilliant one at that — but as such it is not something to be read from cover to cover but explored when needed. It is an essential on the shelves of anyone with an interest in the huge diversity of the insect world, especially, obviously, moths.