Dust of Snow

Robert Frost

The way a Crow

Shock down on me

The dust of snow

From a hemlock tree

Has given my heart

A change of mood

And saved some part

Of a day I had rued.

Find this poem online at Poetry Foundation

Dust of Snow

Robert Frost

The way a Crow

Shock down on me

The dust of snow

From a hemlock tree

Has given my heart

A change of mood

And saved some part

Of a day I had rued.

Find this poem online at Poetry Foundation

This year our Ten Things column will present a selection of words (of five or more letters) with a different ending each month. This month …

Words Ending in -ine

So how many of those words did you know? And how many do you use?

You got to be careful if you don’t know where you’re going,

because you might not get there.

Yogi Berra

Each month we’re posing six pub quiz style questions, with a different subject each month.

As always, they’re designed to be tricky but not impossible, so it’s unlikely everyone will know all the answers – just have a bit of fun.

General Knowledge

Answers will be posted in 2 weeks time.

Our look at some of the significant happenings 100 years ago this month.

13. Birth. Michael Bond, English fiction writer, creator of Paddington Bear (d.2017)

16. A British Broadcasting Company radio play by Ronald Knox about workers’ revolution in London causes a panic among those who have not heard the preliminary announcement that it is a satire on broadcasting.

26. Scottish inventor John Logie Baird demonstrates a mechanical television system at his London laboratory for members of the Royal Institution and a reporter from The Times.

29. Birth. Abdus Salam, Pakistani physicist and Nobel laureate (d.1996)

Wishing everyone a Happy New Year

May you have a healthy, happy, and successful 2026

And let’s see if we can make it better than 2025

And so to notes of things I didn’t otherwise blog about earlier in December.

Tuesday 2

Last Friday on the way home from the osteopath, I stopped at our local flower shop, to procure a large bouquet of chrysanthemums for N. They also had some large Phalaenopsis orchids; some white, some a slightly striped mauve. I indulged in in an orchid for myself! Last evening I looked at it on the bedroom windowsill in the light of my bedside lamp and was struck by the oblique lighting effect. So with my mobile to hand I grabbed a couple of photos.

People think orchids are difficult, and have to be thrown out when they’ve finished flowering. But this is not true of Phalaenopsis. They just have to be treated the right, but simple, way. Although you may never achieve the floral magnificence which the commercial grower achieved, you can get them to repeat flower once or twice a year, for years. Orchids are fairly expensive, so don’t just throw that investment away after a few weeks.

People think orchids are difficult, and have to be thrown out when they’ve finished flowering. But this is not true of Phalaenopsis. They just have to be treated the right, but simple, way. Although you may never achieve the floral magnificence which the commercial grower achieved, you can get them to repeat flower once or twice a year, for years. Orchids are fairly expensive, so don’t just throw that investment away after a few weeks.

Wednesday 3

Cracked open the first bottle of 2024 Tavel (see https://zenmischief.com/2017/11/rose/ for my first post about Tavel). Verdict: really lovely and only a little behind the 2021, which for me was the best vintage ever.

Thursday 4

I managed to opt out of accompanying N to her hospital eye appointment – and by all accounts it’s as well I did as it would have been time wasted because she just got a round of boring tests. So I stayed extra long in the nice warm, comfortable bed, and then failed to do everything I needed to get done.

Friday 5

Gorgeous pink and apricot sunrise this morning.

Sunday 7

Its raining. It’s dull and dreary. It’s miserable. It’s December. And yet we still have roses trying to flower!

Monday 8

Eating lunch today and there appears a squirrel to sit two feet outside the window. What on earth is it carrying? Oh, the remains of an avocado (it’s obviously raided the compost bucket). And it sits there, quite nonchalantly, destroying the skin of this half avocado and throwing fragments everywhere – there can’t have been a lot of flesh left on it, but it was clearly worthwhile.

Wednesday 10

Phew! That was a couple of days slog getting cards and parcels organised and (mostly) away. So nice this morning to drop round to friends for pre-Christmas coffee and mince pies, take their presents, and relax.

Sunday 14

My trail cameras are driving me nuts. They’re set to take photos during darkness. The newest one will not take enough pictures; just a few during the evening and nothing after midnight. It works fine indoors, but not outside. The old one takes pictures OK, but fewer than I would expect, but enough to show the new one doesn’t work well. WTF is going on? Still one thing they produced this week was three foxes in the garden, up near the house; they looked as if one (at least) was an intruder on an established territory.

Monday 15

Last night there were two crane flies on the bedroom ceiling. Why? I know it is fairly mild, but it really isn’t the right time of year. They were obviously Tiger Craneflies (Nephrotoma spp.) from the almost unbelievable, and unexpected, colouring – clearly pretending to be a wasp!

Wednesday 17

Weird pink fog! Very foggy at 04:00 and still foggy when I got up just before 08:00, which was roughly sunrise. Looking east the fog was distinctly pink, presumably due to scattered light from the rising sun. But a very odd effect.

PS. I was indeed right about the pink fog, see for instance this Guardian report.

Thursday 18

Today arrived two Postcrossing postcards. They completed my latest board and take my total to 500 cards received I under three years.  I was wondering if I would manage to complete the board before Christmas, but I had expected it to be a bit more finely judged than this.

I was wondering if I would manage to complete the board before Christmas, but I had expected it to be a bit more finely judged than this.

Sunday 21

This evening we had roast half shoulder of lamb which we’d had sitting in the freezer for a while. And guess what? All three cats came along for a share! None had a lot, just two or three morsels – just a little taster so we’re sure that the humans have been out hunting for us.

Tuesday 23

We saw the gardener today. He was livid with his GP and his specialists – and rightly. They demand this that and the other tests, scans etc.; don’t explain why; and don’t tell him the results without him demanding. Oh and they don’t talk to each other either; but when they do they don’t read the correspondence; and he’s left as a channel for information – especially as he’s caught between three different health authorities! I had to remind him that (a) it is his body and his results so he is entitled to know and should be told; (b) if they can’t provide a good reason for a test (like he has a symptom of something) then he is entitled to refuse to go along with it (you’re entitled to decline anyway); and (c) his GP is the one who retains overall responsibility for his total healthcare. Admittedly I have only his word for all this, but it looks like a classic example of how not to care for your patient. Some body(s) need the application of an Exocet suppository.

Wednesday 24

Last evening we had a small amount of mashed potato left over, which we knew we’d not use in the next couple of days. So with some scraps it was put out for the fox. This morning, everything had disappeared. Who knew that foxes like mashed potato? I’m always surprised at the things the foxes will eat – like digestive biscuits! But we do know that cats like prawns; so needless to say our three felines helped this evening with our prawns. Sorry, foxes, you didn’t get a chance.

Thursday 25

Christmas Day, and what a glorious sunny morning with not a cloud in the sky – but breezy and chilly. An Alpine day, except there’s no snow. And it has been deathly quiet here all day.

Friday 26

Boxing Day, and still the commercial world are pushing out routine emails. Yesterday (Christmas Day!) and today I’ve had four emails about our bank accounts, several about upcoming auctions, and at least one reminding me of an upcoming subscription renewal, plus a number of others. All could have waited until Monday.

Sunday 28

This afternoon I unloaded the last two weeks photographs from the trail cameras to find a couple of super shots.

First there was one from 19/12 of the fox going over the 6ft fence to next door, with apparently no effort. The thing is that the guy next door probably thinks that the fox can’t manage his fence.

The thing is that the guy next door probably thinks that the fox can’t manage his fence.

Then in the small hours of Christmas morning something I’ve not seen before: two foxes having a jousting match (probably over territory).

Tuesday 30

“It was that prolonged, flat, cheerless week that follows Christmas … those latter days of the dying year create an interval, as it were, of moral suspension: one form of life already passed away before another has had time to assert some new, endemic characteristic. Imminent change of direction is for some reason often foreshadowed by such colourless patches of time.”

[Anthony Powell; The Acceptance World]

Wednesday 31

So the old year ends with a bright, sunny, but cold day. Which makes a refreshing change from the rest of this dismal year. Hopefully it’s a good omen for 2026 – I certainly hope so! As usual I’m not making New Year Resolutions as I view them as self-defeating ordinances, but that doesn’t mean I won’t be trying to tweak and enhance things. I’d love to be able to start with killing the depression. Perhaps I need to invest in a few sacrificial Gadarene Swine.

And so this year’s final collection of links to items you may have missed …

Science, Technology, Natural World

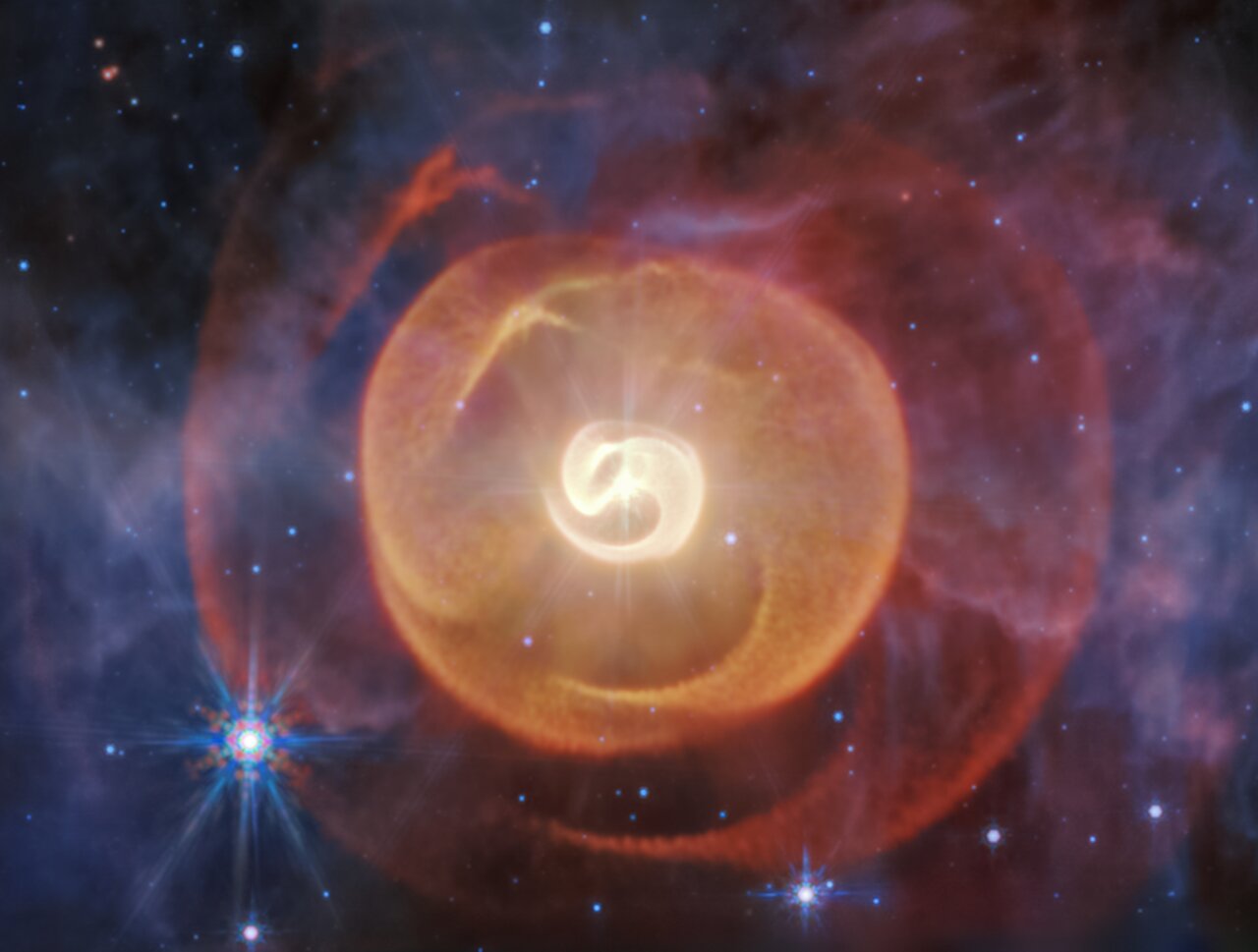

Let’s start off with some seasonal stars … Here are three stars embroiled in an odd ménage à trois (below).

After which the James Webb Space Telescope has spotted a manger for exomoons. [££££]

There’s a huge, faint nebula near Andromeda, but now researchers have managed to work out how far away it is.

Now down to Earth … Here are two reports on the somewhat surprising story of how we were domesticated by cats. First from Scientific American [££££] and the second from the BBC.

Research into the remains of ancient DNA have revealed the carrier of the world’s earliest known plague.

Here’s a little experiment to do at home: how close you can get to the value of π (pi) by repeating Buffon’s needle experiment.

Lastly in this section, here’s something I actually saw … pink fog. It was very odd and rather eerie.

Health, Medicine

When should we undertake mass screening, and when shouldn’t we?

Sexuality & Relationships

So just how monogamous are humans? And where are we in a league table of species?

Social Sciences, Business, Law, Politics

Let’s hope this isn’t the thin end of the wedge … the Danish postal service is to stop delivering letters.

Art, Literature, Language, Music

For those interested in language, here’s a brief look at the history of the word c*nt.

Here’s a look at the 2000+ history of sex workers in art. [LONG READ]

Musicians and scientists are now understanding and recreating the sound of music from the Stone Age. [LONG READ]

Meanwhile shells found in Spain could be among oldest known musical instruments.

History, Archaeology, Anthropology

In Bolivia they’ve uncovered over 16,000 dinosaur tracks – that’s the largest such known field.

It’s being suggested that an ancient hominin called Little Foot may be a newly recognised species.

Still on palaeontology, finds at a site in Suffolk are suggesting that humans made fire some 350,000 years earlier than previously thought.

Ever onward … and a new study is suggesting people arrived in Australia 60,000 years ago.

Archaeologists have found yet another massive structure close to Stonehenge.

While at the other end of the country archaeologists have found a 3,000-year-old mysterious mass burial site in Scotland.

Here’s something I thought we already new … Ancient Roman cement from Pompeii is revealing the secrets of its durability. [££££]

New DNA work on a Roman era young woman found in southern England has revealed that she wasn’t dark skinned after all.

Now here’s an odd one: it is being suggested that the Black Death plague which swept Europe in 14th-century was triggered by a volcanic eruption.

London

Matt Brown is continuing his work on mapping with a big update to his map of Anglo-Saxon London.

In other work Matt Brown takes a look at the forgotten Thorney Island, now know as Westminster.

Lifestyle, Personal Development, Beliefs

Here are some thoughts on the way in which hospitality can bruise us mentally and emotionally.

Shock, Horror, Ha ha ha!

Finally for this year, two amusements …

First, the Official Naturist Code.

And then a look at the curious biology of Santa Claus’s elves.

In 1290 Queen Eleanor, wife of King Edward I, died at Harby, Nottinghamshire, and her body was carried to London to be buried in Westminster Abbey. Edward had a memorial cross erected near each religious house where her body rested overnight on its journey to London. This cross at Geddington in Northamptonshire is one of the remaining three. I was brought up at Waltham Cross, which has another of the remaining crosses – hence my interest. Find more about this piece of English history at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eleanor_cross, and in the text of my late father’s talk from the mid-1950s.