This is the first of four articles addressing nudity and society. Although a series, the first three will stand alone; the fourth article will be a selection of useful supporting links. Consequently there will be overlap of material between the articles. The articles are not fully referenced (hence Article IV), although a Google search on “nudity society body acceptance” (or similar) will find many articles (academic and otherwise) relevant to the whole series, starting perhaps with British Naturism’s 2020 Submission to Parliament.

Every one of us has a body, but the simple act of showing it – or even talking about it – can set off a storm of reactions. In some parts of the world, a bare shoulder or a topless photo will cause moral panic, outrage, or even legal trouble.

So why is nudity such a big deal? Because it hasn’t always been. Homo sapiens has been wearing clothes for only the last few thousand years, or an estimated 1-2% of the species existence.

As recently as the Ancient Greeks the human form was celebrated as a thing of strength and beauty. Their statues and athletes were unapologetically nude, and there was nothing inherently scandalous about it.

However as religion and moral codes evolved – particularly through the Abrahamic religions – the idea of nakedness became entangled with sin and shame; and over time we came to see our skin as something to be hidden, controlled, or covered. And the mindset stuck.

Most of us are taught as children being naked is something to be embarrassed about, and we’re conditioned to see nudity as dangerous; it instantly crosses some invisible moral line.

Such conditioning confuses the natural with the sexual. The human body can, of course, be sensual, but it’s still human. It eats, breathes, moves, and ages! – although it’s rarely represented that way in mainstream media. Instead it’s airbrushed, idealized, and used to sell everything from perfume and lingerie to cars and kitchen refits.

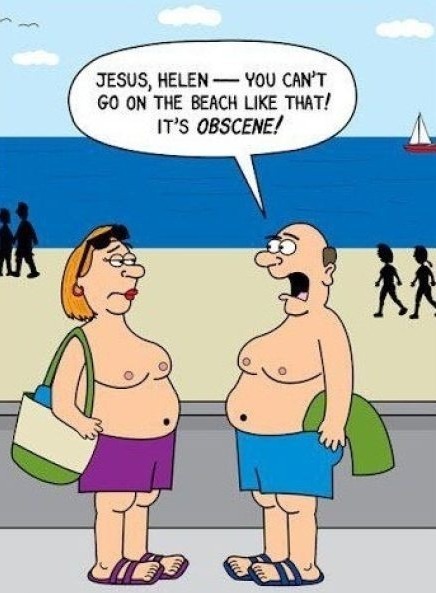

Not everyone experiences these double standards the same way. Women’s bodies, in particular, have been both glorified and policed for centuries. For example there’s the current-ish debate around #freethenipple: men can go shirtless in public without a second thought, but when women do the same, it’s indecent or provocative. It’s a small example of a much larger issue – the use of modesty to enforce social control, especially over women.

Cultural differences play a huge part in this. In some communities – especially indigenous or equatorial societies – nudity isn’t shocking or taboo; it’s practical; even ordinary. By contrast in most of the West, it’s still wrapped in moral judgment. Religion, tradition, and colonial history all shape how we decide what’s “appropriate”, even if the rules no longer make much sense. The

taboo is supposedly to protect children from seeing anything not “age appropriate” – which means essentially anything the child’s parents/guardian may be uncomfortable with.

Art, however, provides an interesting contradiction as restrictions mostly don’t apply in public museums or art galleries. Nude art has been celebrated for centuries; it’s beautiful and pure: as long as it’s in a museum. But when similar images appear in the media, they’re labelled obscene. The line between “artistic” and “inappropriate” shifts continually, thus revealing our that discomfort isn’t really the body itself but about context and control. Only half jokingly, I often say that a B&W nude photograph is art; but in colour it’s pornography.

The recent rise of the body positivity and naturism movements has tried pushing back against all this. The message is simple: seeing real, unfiltered bodies makes us more accepting of ourselves and others. If we stop treating nudity as shameful and inappropriate, we’ll stop treating our bodies as problems to be fixed. But old habits die hard, and society’s obsession with modesty and image continues to dominate.

So why is nudity such a big deal? The answer is essentially because it sits at the crossroads of morality, power and identity. Our discomfort with the naked body says less about the body and more about the cultural stories told about it. Questioning those narratives can lead to a healthier and more honest relationship with ourselves and others.

Although they seldom realise it, what really makes people uncomfortable isn’t the naked body itself, but the vulnerability and honesty that come with it.