The names people have are an endless source of fascination, and for the professionals as much as us mere mortals. During their work hunting the heirs to unclaimed estates, genealogy firm Fraser and Fraser have uncovered some truly bizarre names perpetrated by the Victorians. Amongst them are:

Leicester Railway Cope, who was so named because he was born on a carriage at Leicester Train Station in 1863.

Time Of Day, son of Thomas and Alice Day. Apparently the title was a family tradition.

Windsor Castle. Clearly a family with regal pretensions: her father’s surname was Castle and her mother’s maiden name was King.

That’s It Who’d Have Thought It Restell, who later changed his name to George Restell.

Zebra Lynes, the daughter of James Lynes, a basket maker from Southampton.

You can find a few more, as well as images of the offending Birth Certificates at www.buzzfeed.com/lukelewis/insane-british-names-from-the-19th-century.

Unfortunately my ancestry doesn’t run to anything more exotic than Farclay Hicks, who was my 4x-great-grandfather.

Category Archives: people

Weekly Photograph

Weekly Photograph

This young lady was accosting motorists to wash their windscreens on the A40 westbound at Savoy Circus lights. She was not impressed with being photographed — I wonder if she is doing something illegal? I always try photographing these people, partly to try to deter them and partly because I do so enjoy pissing them off.

Windscreen Washer Bottle 1

Acton; June 2015

Click the image for larger views on Flickr

Dora Marshall (1915-2015)

Last Wednesday (17 June 2015), on a beautiful sunny day, we interred my mother at Colney Wood Burial Park on the outskirts of Norwich, in a plot in the wood which she had chosen when my father died in 2006. This is what she wanted, and what a delightful place it is: mature English woodland, filled with wild flowers (magnificent foxgloves over 1.5m high) and birdsong.

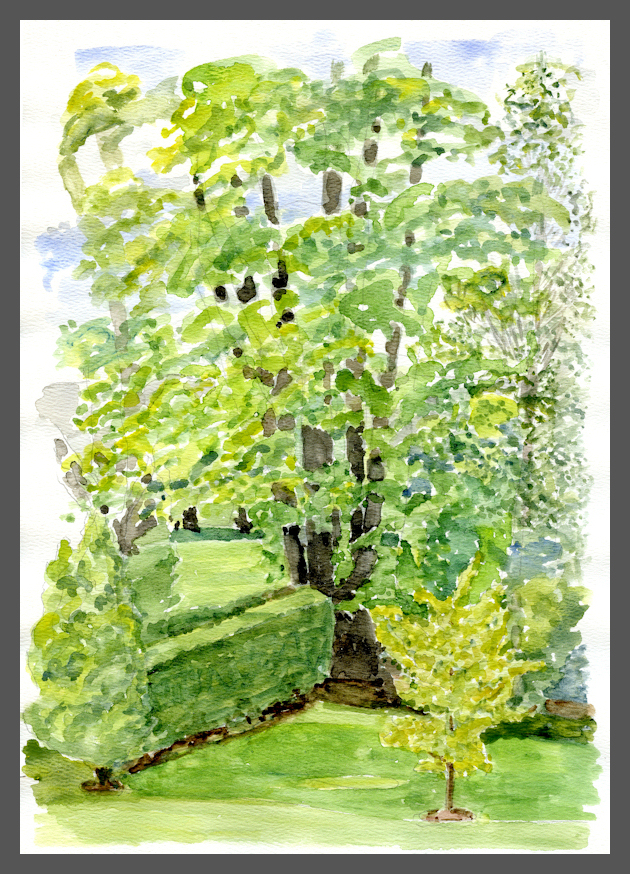

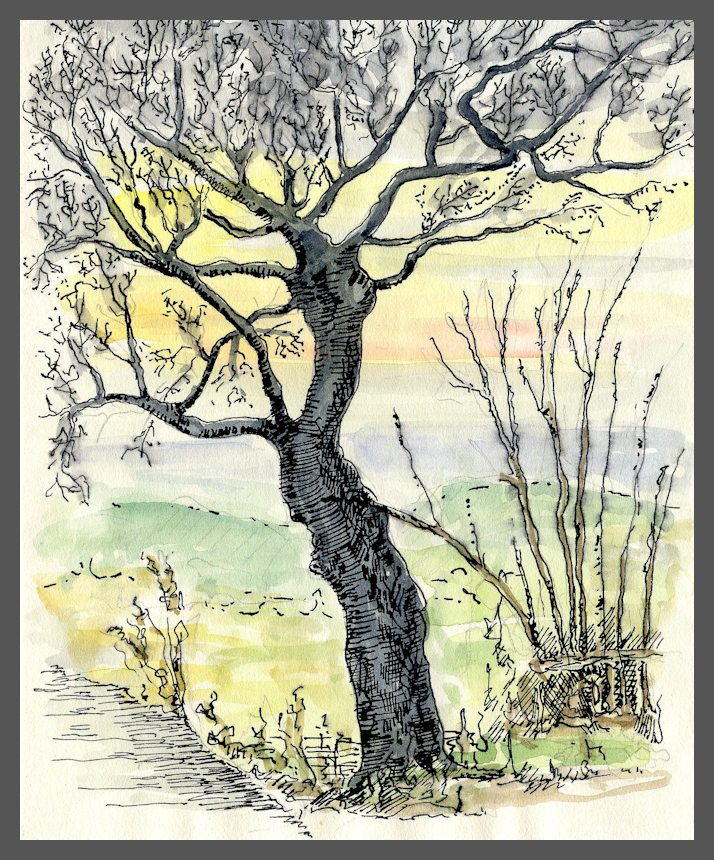

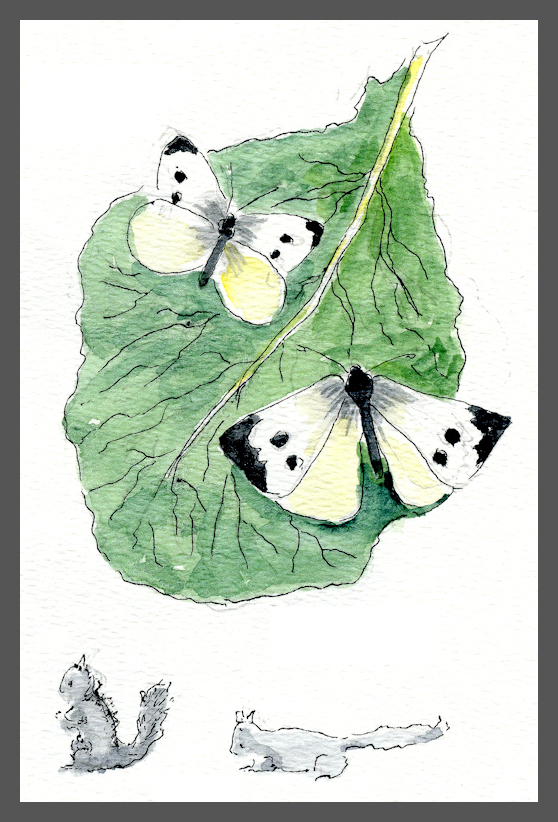

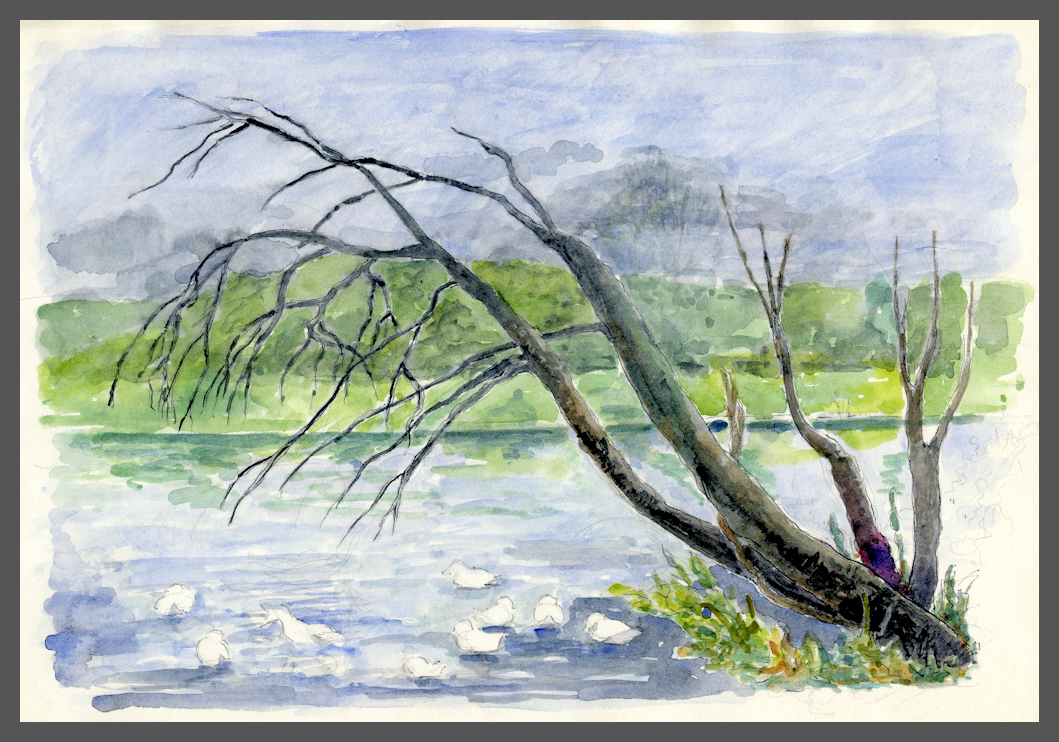

The short, simple, secular service which preceded the burial was a celebration of my mother’s life — including a small display of her artwork — for she packed much into her 99 years. I promised a number of friends I would post here a copy of my address. So give or take an inevitable ad lib or six this is what I said, interspersed with tiny reproductions of a few of Dora’s watercolours (click the images for larger views).

Welcome, everyone and thank you for joining this small celebration of my mother’s life. And a small celebration is appropriate as Dora was a small, quiet lady, but someone who did everything her way and never gave up.

I was reflecting a few days ago and realised that for most of our lives we see our parents as being normal, ordinary people; and it is only looking back, at times like this, one comes to realise just how amazing and talented they really are. And as many people have said over the last few weeks, Dora certainly fits the category of amazing and talented.

Dora Cullingworth (a rare surname, it’s from the village in Yorkshire) was born on 12 October 1915 in Highgate, London where her father had a wood yard. However within two years they moved to Canvey Island — where her grandmother already had property — to escape the then new-fangled bombing of London by the Germans.

Dora Cullingworth (a rare surname, it’s from the village in Yorkshire) was born on 12 October 1915 in Highgate, London where her father had a wood yard. However within two years they moved to Canvey Island — where her grandmother already had property — to escape the then new-fangled bombing of London by the Germans.

Dora always talked fondly of Canvey and clearly enjoyed her childhood there, where her three younger sisters — Olive, Vera and Joan — were born. The family remained there until around 1924 when they moved to Twickenham and her father took up employment as a saw doctor and foreman with the family firm, Alsford’s the timber merchants (which is sadly no longer in the family) — the Alsfords were her aunts, uncles & cousins by marriage via her father.

It must have been at this time, when Dora changed schools, that she was forced to change from being naturally left-handed to write right-handed. She became ambidextrous and was just as able to write and paint with either hand.

In those days girls often didn’t get much by way of education and Dora left school on her 14th birthday to start work as a shop assistant at the Scotch Wool Shop in Teddington. She must already have been able to sew and knit, but here she would have developed those skills.

She developed other skills too: in her late teens and early twenties she took herself to art school in the evenings — learning calligraphy, pottery, drawing and painting — both watercolour and oils. Among her artwork we still have an oil self-portrait of her from when she was about 21 — not here today as it is currently being restored and reframed.

She developed other skills too: in her late teens and early twenties she took herself to art school in the evenings — learning calligraphy, pottery, drawing and painting — both watercolour and oils. Among her artwork we still have an oil self-portrait of her from when she was about 21 — not here today as it is currently being restored and reframed.

Dora must have been especially meticulous, neat and precise — something she never lost — as in 1936 she went to work at the National Physical Laboratory (The Lab) in Teddington as a draughtsman’s tracer. Remember in those days every engineering or architectural drawing was drawn — and redrawn, and redrawn, and redrawn — by hand; there being no modern computer-based CAD systems. Dora was obviously good at her job as one of her bosses later described her as “a princess among tracers”.

It was at The Lab that Dora met Noel David George Vincent, an engineer. They married in May 1939 and, as young married women did then, Dora stopped work … that is until the outbreak of war, when in November 1939 she was one of the first married women to be re-employed at The Lab.

During the late 1930s Dora spent several holidays cycling in Europe; she talked fondly of summers in France, Switzerland and southern Germany. Indeed I still have her passport, issued on 1 June 1939, when she was newly married, which contains an illegible border stamp from later that same month — and we have found a small watercolour of the roof-scape in Orange, France dated Summer 1939.

She and Vincent must also have spent time Youth Hostelling in this country, for in 1943, after a lot of string-pulling, she left The Lab and became Warden of the YHA hostel in Leatherhead.

Here she met my father (Bob; who is also buried here), and at the end of the war they were living together, as man and wife, in Camden. Needless to say Vincent petitioned for divorce, citing my father as co-respondent; this was granted in August 1947 and a month later Bob and Dora married.

Here she met my father (Bob; who is also buried here), and at the end of the war they were living together, as man and wife, in Camden. Needless to say Vincent petitioned for divorce, citing my father as co-respondent; this was granted in August 1947 and a month later Bob and Dora married.

In the autumn of 1950, with yours truly well on the way, my parents turned themselves inside out financially to buy a small terraced house at Waltham Cross (just in Hertfordshire). I appeared in the January.

Despite being hard up and struggling to pay their mortgage, my father wouldn’t let my mother work after I was born. But always being her own person she made the best of a bad job. Yes, her days were organised to support my father (and me) but she ensured that on most days she had finished housework by lunchtime and had the afternoon to spend as she pleased.

At various times in the 50s and 60s I remember Dora going to art classes at the local technical college, to pottery classes and even an odd hairdressing course. In the summer she would spend her afternoons sitting in the garden, in the sun — something which would catch up with her in old age as skin cancer.

Or her afternoon would be spent making jam, bottling fruit, making wine or beer, or tending the small vegetable plot in the garden.

Or her afternoon would be spent making jam, bottling fruit, making wine or beer, or tending the small vegetable plot in the garden.

As the years wore on Dora became more interested in natural history. The interest had always been there and I recall many weekend cycling trips; there were walks in the woods, across the marsh and to the park; all the while being taught about the natural world, churches and history. There were picnics too; and summer trips to the local outdoor swimming pool. All of which gave me a wonderfully bohemian and eccentric upbringing.

Dora started taking afternoon walks round a local lake (actually a pre-war abandoned gravel pit) — birdwatching, hunting flowers and insects — which led to her nature diaries. Along with this there were the forays into photography — including developing and printing her own films, and even building a simple photographic enlarger! — plus picture framing and book binding.

Dora was all this time sewing and knitting (she made most of my clothes until I was about 10), doing embroidery, painting — mostly small watercolours — and reading. The art, of course, flowed across into the nature diaries which she wrote in her small very neat hand, and illustrated with little watercolours and photographs. We have some 30 volumes of annual nature diaries — all written, illustrated and bound by Dora!

She was happy doing her own thing, as and when she wanted. She was never very sociable or demonstrative, something which irked my father as it stopped him getting on in local politics. But he irked her too: it would have needed a big adjustment when my father was working from home for the last 2 or 3 years before he retired; having him under foot all the time must have been some species of purgatory for Dora. But in true style she said little and just got on with what she wanted to do.

She was happy doing her own thing, as and when she wanted. She was never very sociable or demonstrative, something which irked my father as it stopped him getting on in local politics. But he irked her too: it would have needed a big adjustment when my father was working from home for the last 2 or 3 years before he retired; having him under foot all the time must have been some species of purgatory for Dora. But in true style she said little and just got on with what she wanted to do.

In 1988 Bob and Dora felt they had outgrown Waltham Cross and moved here to Norwich. They bought a bungalow in Bowthorpe where Dora continued doing what she loved: gardening, observing nature, painting and photography — aided and abetted by walking their small dog.

Dora cared for my father in his last few years and after he died in 2006 — when she was already 90 — she stayed in the bungalow, on her own, doing essentially everything for herself, for another four years. Luddite to the last she never had a washing machine, freezer or microwave — she didn’t even have a spin-dryer until she broke her arm in 1980!

Finally at the age of 94 she admitted everything was too much, and she chose to move to Carleton House. There, with everything being done for her, she had a wonderful 5 year holiday, with time to do whatever she wanted, when she wanted: reading, sewing, knitting, drawing, painting or just watching nature go by. I remember her telling me a couple of years ago about sitting in the garden at Carleton House one Spring afternoon watching a couple of hares gambolling around the lawn. She was in the country, which is what she wanted. Right until the end she would read almost anything we brought her, she was making soft toys — special line in Humpty Dumpty — and painting all her own greetings cards!

Finally at the age of 94 she admitted everything was too much, and she chose to move to Carleton House. There, with everything being done for her, she had a wonderful 5 year holiday, with time to do whatever she wanted, when she wanted: reading, sewing, knitting, drawing, painting or just watching nature go by. I remember her telling me a couple of years ago about sitting in the garden at Carleton House one Spring afternoon watching a couple of hares gambolling around the lawn. She was in the country, which is what she wanted. Right until the end she would read almost anything we brought her, she was making soft toys — special line in Humpty Dumpty — and painting all her own greetings cards!

Sadly her independence and stubbornness eventually let her down: a fall resulting in a broken hip. Despite Dora’s frailty she was still relatively fit and had some mobility, so the medics decided to operate to fix the hip and hopefully get her mobility back. We all knew it was a risk and it turned out to be a risk too far. At 99 the fall and the operation proved just too much for Dora’s body and she faded over a period of a week.

Which is as she would have wanted it: in full control of her mind and active until the last, then a peaceful end.

Well Dora always did say she wanted to “wear out” rather than “rust out”.

And having finally worn out, that small, quiet lady has left a huge hole in all our lives.

May your god go with you.

For anyone who is interested I have uploaded a copy of the Order of Service to my website.

Images © Dora Marshall, 1980-2015

Weekly Photograph

So there I was in Uxbridge a few weeks ago, sitting waiting people watching while for Noreen to emerge from M&S, when these three beauties happened along. They seemed to be about to enact Act 1, Scene 1 of Macbeth.

Macbeth Act 1, Scene 1 in Modern Dress

Uxbridge, March 2015

Click on the image for larger views on Flickr

Weekly Photograph

Weekly Photograph

This week’s photo was taken last October when Noreen and I travelled on the paddle-steamer Waverley from London (Tower Pier) to Southend. This guy was one of the passengers. He was totally oblivious to me sitting on deck less than 10 feet away taking his photo. I don’t know how he was warm enough in just a t-short at 9AM on a cold foggy morning. I ask you, what does he look like?!

Plonker

River Thames, October 2013

Weekly Photograph

This week’s photograph was taken last summer while sitting outside a pub in London’s Covent Garden. The guy spend quite some minutes ferreting around his pockets while making mobile phone calls, it appeared all in aid of paying for parking his motorbike. It was street performance at it’s best — completely impromptu!

Contortionist

Covent Garden; August 2013

Weekly Photograph

One of my photographic interests is just sitting somewhere and quietly photography the people who go by.

Yes, before you ask, this is perfectly legal in the UK — you may legally photograph anything or anybody in public or on a railway station (and this includes children) without asking permission — the only exception is if a police officer considers you are photographing something pursuant to an act of terrorism. Moreover no-one except a police officer with a search warrant has the right to confiscate images or equipment or demand you delete images.

Surprisingly in all the years I’ve been quite openly taking photographs in the street and on stations I have only twice been harangued by a member of the public (both of whom thought I was doing something illegal — I wasn’t) and twice approached by a police officer. Both officers agreed that I was doing nothing illegal, although one (who was armed) wasn’t very happy as I was taking photographs near (but not of) some Arab embassies.

A few days ago I was sitting drinking coffee on London’s Paddington Station and was close to the YO! Sushi bar so I couldn’t resist photographing the chefs …

Click images for larger views on Flickr

Sushi Girl (left) and Sushi Boy

Paddingtom Station, London; June 2013

Book Review

Michael Barber

Brief Lives: Evelyn Waugh

(Hesperus; 2013)

When Michael Barber first told me he had a biography of Evelyn Waugh being published, my first reaction was “Why?”. Why do we need another biography of Waugh?

When Michael Barber first told me he had a biography of Evelyn Waugh being published, my first reaction was “Why?”. Why do we need another biography of Waugh?

But then when I got a copy I realised this isn’t really a biography but more a dozen or so quick sketches of the man, for what Hesperus are doing is creating a series of “short, authoritative biographies of the greatest figures in literary history; written by experts in their fields to appeal to general readers and academics alike”.

Given that this is the aim, then Barber and Hesperus have largely succeeded. This is a short work which is well and amusingly written, while remaining interesting, light, accessible and, I found, quite hard to put down.

Yes, the book lacks detail — but what does one really expect in 120 pages? However, although I am no expert on Waugh, it did seem to encapsulate the essence of the man and his life: idiosyncratic, snob, arriviste, poseur, spendthrift, drunk, intransigent bore and grumpy old man (even when quite young); but also both an excellent novelist (I’ll except Brideshead Revisited which never worked for me) and often highly amusing.

As a bonus, at least for me, Anthony Powell gets quite a few mentions. Powell and Waugh, although in some ways rival writers, were friends and admired each others’ work — both publicly and privately — often writing to say how much they had enjoyed the other’s latest volume. Waugh always wanted to live to see Powell complete Dance, but sadly he died halfway through. Wouldn’t it have been interesting to have heard his views on the second half of Dance? How the war trilogy compared with his Sword of Honour? And what would he have made of the denouements of Temporary Kings and Hearing Secret Harmonies?

As Anthony Powell so often did I shall conclude this review with two gripes. While understanding that publishers need to keep costs down, such awful cheap paper is horrid to handle and isn’t going to stand the rigours of time; I would happy to pay an extra 50p to £1 on the price of a book if it meant more aesthetically pleasing paper.

Finally I deplore the lack of an index. I know this is a short work, but any non-fiction book without an index becomes unusable as a reference source. And that, to my mind, is inexcusable in an environment where we must do everything we can to encourage the use of books as a resource. Again I have to lay the blame on cost-cutting publishers, rather than the authors, most of whom I suspect would (privately, at least) agree.

An excellent introduction to the man and a highly enjoyable and interesting read.

Overall rating: ★★★★☆