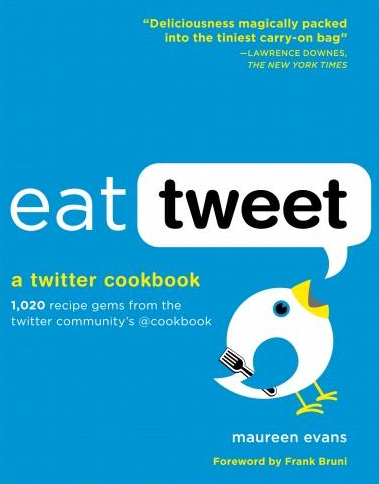

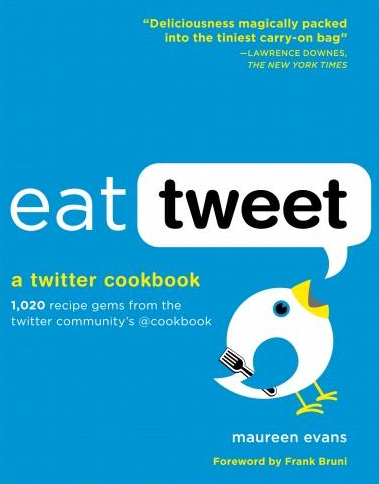

Maureen Evans

Eat Tweet: A Twitter Cookbook

Artisan; 2010

According to the blurb on the over of this book Maureen Evans was the first person to tweet recipes — not surprising as her partner is Blaine Cook the original programmer on Twitter.

According to the blurb on the over of this book Maureen Evans was the first person to tweet recipes — not surprising as her partner is Blaine Cook the original programmer on Twitter.

Using her Twitter account @cookbook, since 2006 Evans has condensed many recipes into the 140-character Twitter format, and along the way gathered 223,000 followers! Yes, with a little ingenuity recipes can be condensed into this tiny format, as this “pocket book” of 1020 recipes proves. And it’s fun too, in a geekish sort of way.

The book is divided into the usual sections: Vegetables, Soups, Main Courses, Cakes, Bread, Drinks etc.; there are also sections on how to read the recipes, tools, conversion charts — the latter necessary as being Canadian Maureen Evans measures everything in cups (also more concise for the Twitter format) and °F. The recipes are generally designed to serve 3-4 normal adults. Apart from the introductory material there is little text other than hints and tips interspersed with the recipes, of which there are 4 to 6 to a page. And nothing in the way of illustration. But in this context somehow it doesn’t matter.

Having said that, this could be the only cook book you’ll ever need, because Evans covers nigh on everything — certainly more than enough to always eat well. And it really is everything … from the basics of stuffing and roasting your turkey, which is actually two recipes:

Stuffed Turkey: Rmv giblets(use in Turkey Stock),rinse,pat dry(+inside). Lightly stuff main/neck cavities. Skewer-shut neck; cross,tie legs.

Roast Turkey: Put StuffedTurkey on roastrack; baste every 30m@325°F 3-3½h for 5-8lb; 3½-4h for 9-12lb; 4-6h for 13-16lb until thigh>165°F.

all the way to some lovely puddings:

Rødgrød med Fløde: Boil3c h2o/c berries &freshcurrant&cherry/c sug. Sieve; +mixd ½c strch&h2o. Stir@med until thick. Top w whipdcrm.

and cake:

Chocolate Decadence Cake: Mlt2c choc/⅔c buttr; beat+⅔c coffee&flr&cocoa. Cream c sug/3egg. Fold all; fill sqpan. 40m@350°F in bainmarie.

Have I tried any of the recipes? No. Do I need to try any of the recipes to know they work? Also no. They are so simple it’s obvious they will work well. OK so perhaps Evans has picked relatively simple recipes, but she is a cooking geek and you can be sure she, and all her Twitter followers, will have tested the recipes to destruction before they hit the book!

Are there omissions? Yes of course; there are omissions in every cook book. For instance there is no mention of Jerusalem artichokes; pheasant; quail; or gammon; nor does my favourite Garlic Roast Potatoes get in. Oh OK, so here is my Garlic Roast Potatoes, in the style …

Garlic Roast Potatoes: Chop 12-16 sm taters 1″ pces. Toss w 2T chopd garlic/T chopd rosemry/2T oil/s+p. Foil parcel. ~40m@200°C

So you may not find your very favourite recipe, but you’ll find something equally as good! And you’ll have a fun time as well!

Overall Rating: ★★★★★

According to the blurb on the over of this book Maureen Evans was the first person to tweet recipes — not surprising as her partner is Blaine Cook the original programmer on Twitter.

According to the blurb on the over of this book Maureen Evans was the first person to tweet recipes — not surprising as her partner is Blaine Cook the original programmer on Twitter. The first thing we need to get straight is that, although it contains recipes, this is essentially not a recipe book. Nor is it a book specifically about ingredients.

The first thing we need to get straight is that, although it contains recipes, this is essentially not a recipe book. Nor is it a book specifically about ingredients.

This book looks at a variety of aspects of this god; at what some of the Zen teachings say; and where Warner says they have hitherto been poorly interpreted. The book also looks at the ways and times Warner has encountered this god in the world. He also touches on the philosophical concepts of the meaning of life and the afterlife. Unsurprisingly there is a lot of Brad Warner in the book as he develops nearly all the 22 short chapters from a real worldly experience.

This book looks at a variety of aspects of this god; at what some of the Zen teachings say; and where Warner says they have hitherto been poorly interpreted. The book also looks at the ways and times Warner has encountered this god in the world. He also touches on the philosophical concepts of the meaning of life and the afterlife. Unsurprisingly there is a lot of Brad Warner in the book as he develops nearly all the 22 short chapters from a real worldly experience.