Another selection of the interesting and curious you may have missed. As usual, science-y stuff first and a rather more mixed bag than normal.

Did you know that for about 2 months of every year there is no night in the UK? No neither did I! This from IanVisits back in May.

Ants that eat electricity are heading for London. No it is 1st April!

[Phobia warning] While we’re on insects, scientists have found a gargantuan aquatic insect in China.

A very rare calico lobster has been caught off the coast of Maine. Rather attractive isn’t it! It’s still alive and on display in an aquarium, but will be returned to the sea later in the year.

On to things that are slightly more concerning. Apparently the environmental cost of beef is ten times that of other meat. But why didn’t they include lamb?

Next an interesting piece on why most of our domesticated animals have floppy ears.

My body makes funny noises. Yours probably does too, but maybe different ones. But why do bodies do these strange things?

Does your rainbow smell? As a “normal” person I find it hard to imagine what synaesthesia must be like. Here are a few insights.

Going back to food for a moment … Scientists are finding a surprisingly complex world of microbes in cheese rind. Yep, that’s what makes all these cheeses taste different.

It looks as if we may have been, and still are being, seriously misled all these years into thinking fat is harmful. Scientists are now suggesting this really isn’t so and dietary advice needs to be changed. Duh!

So stepping quickly into the world of medicine … On how the Great War helped create the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic.

At last some people are beginning to understand the way things work. Here’s a medical study which underlines that decriminalising sex work actually reduces HIV infections as well as violence etc.

Next up we have two interesting articles looking at whether women should or shouldn’t shave areas like legs and armpits: the first by Hadley Freeman in the Guardian; the second by Lucy Brisbane in the Evening Standard. Basically don’t fall into the trap of doing it because fashion etc. say you should. But think about it and shave or not, depending on whether you actually want to, not because of fashion or other people’s attitudes. Be yourself and remember the old adage: “Those that matter don’t mind, and those that mind don’t matter”.

For the historians amongst you, an interesting new theory on how our legends really began.

We’ll gradually bring the historical pieces up to date, so next a look at the naughty and scatological world of medieval marginalia.

A soldier’s lot hasn’t actually changed that much since the Battle of Hastings. Photographer Thom Atkinson displays the essential soldiering kit as it evolved over the last millennium.

Our favourite London cabbie reachee the end of his series on Waterloo Station with a look at the advent of the Eurostar terminal.

This has to be crazy museum piece of the year: an exhibition of broken relationships. Well it is in Brussels.

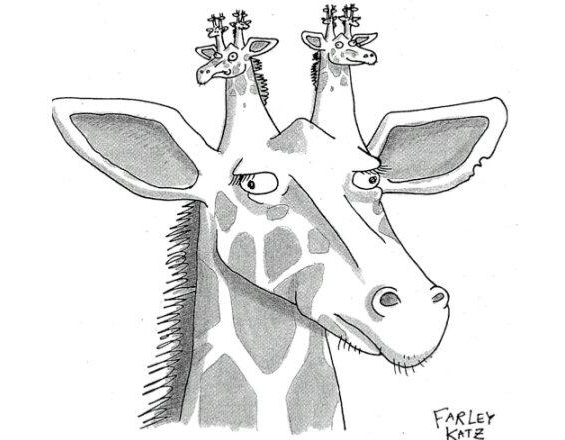

And finally I’ll leave you with two amusements. First a fractal giraffe. Secondly a display of tooth jewellery.

Anchors away!

Sam Kean

Sam Kean