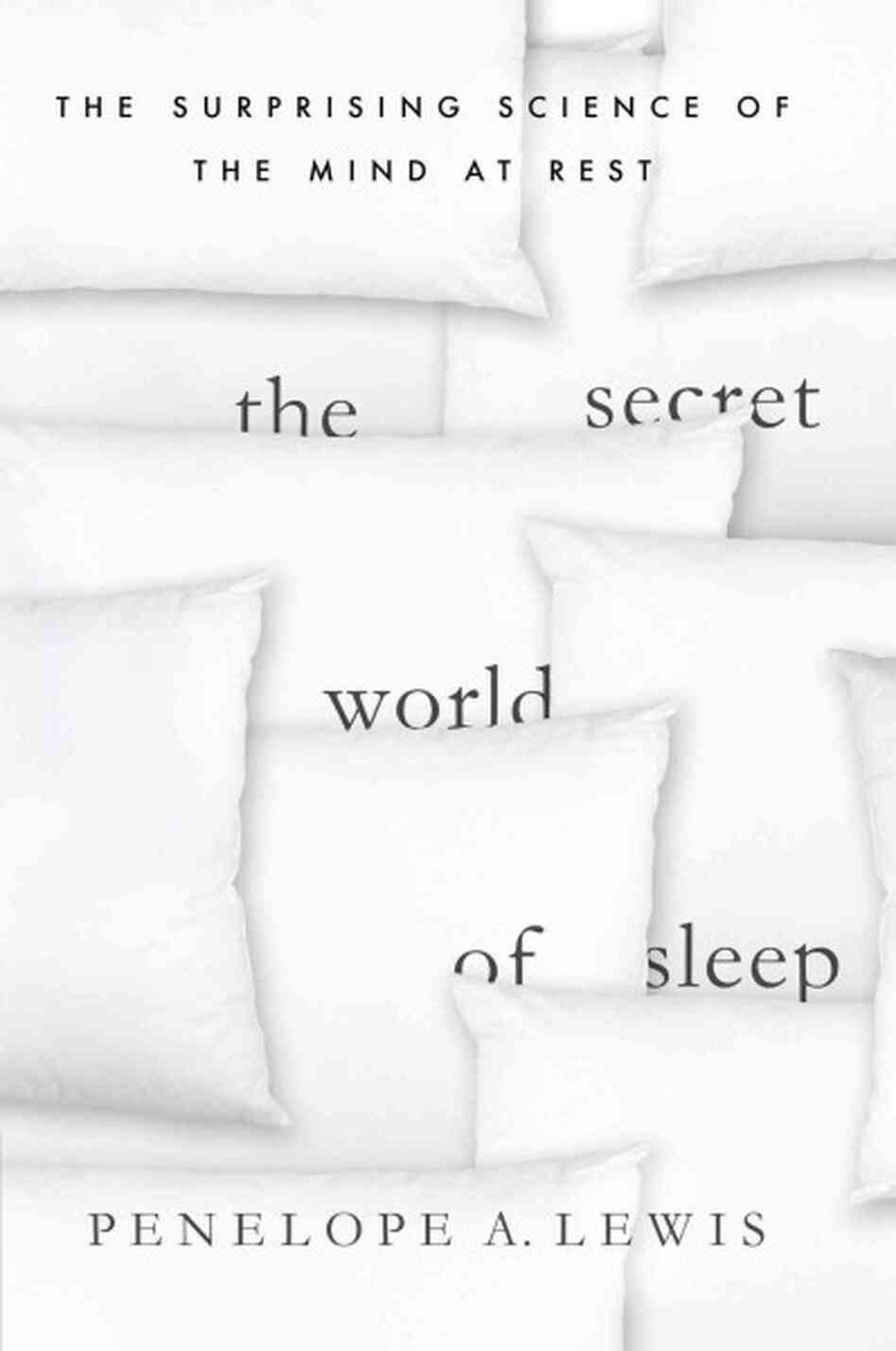

Penelope A Lewis

The Secret World of Sleep: The Surprising Science of the Mind at Rest

Palgrave Macmillan, 2013

This is another of those books which I wanted to read and which appeared for either Christmas or my birthday (I forget now which as they are quite close together). This is what the cover blurb says:

A highly regarded neuroscientist explains the little-known role of sleep in processing our waking life and making sense of difficult emotions and experiences.

In recent years neuroscientists have uncovered the countless ways our brain trips us up in day-to-day life, from its propensity toward irrational thought to how our intuitions deceive us. The latest research on sleep, however, points in the opposite direction. Where old wives’ tales have long advised to “sleep on a problem,” today scientists are discovering the truth behind these folk sayings and how the busy brain radically improves our minds through sleep and dreams. In The Secret World of Sleep, neuroscientist Penny Lewis explores the latest research into the nighttime brain to understand the real benefits of sleep. She shows how, while our body rests, our brain practices tasks it learned during the day, replays traumatic events to mollify them, and forges connections between distant concepts. By understanding the roles that the nocturnal brain plays in our waking life, we can improve the relationship between the two and even boost creativity and memory. This is a fascinating exploration of one of the most surprising corners of neuroscience that shows how science may be able to harness the power of sleep to improve learning, health, and more.

Yes, OK, I guess it does do all of that and at a level which is likely OK for the intelligent layman. But as a scientist I found it somewhat lacking, or maybe more correctly it felt loose, in the details. I don’t profess to be very knowledgeable about the neurology of sleep, but I had the feeling that there was more there which is known and which would tie everything together. I may be wrong, and in fairness to Lewis she does say at a number of points “we don’t know how this works”.

Yes, OK, I guess it does do all of that and at a level which is likely OK for the intelligent layman. But as a scientist I found it somewhat lacking, or maybe more correctly it felt loose, in the details. I don’t profess to be very knowledgeable about the neurology of sleep, but I had the feeling that there was more there which is known and which would tie everything together. I may be wrong, and in fairness to Lewis she does say at a number of points “we don’t know how this works”.

Did it tell me anything I didn’t know? Well nothing which I found helpful and which has stuck sufficiently that I could recite it now. As always, yes, OK, I’m probably way above the audience this was written for. I found it an easy but not compelling, or gripping, read — sufficiently so that I whizzed through it far faster than I had expected.

All of this is a shame because I wanted to get that “Wow!” inspirational insight and it didn’t happen. I still feel it should.

As with many modern books it is a slim volume (about 190 pages) and it could have been much slimmer: as always there is too much white space on the page. Even if you don’t want to reduce the font size the leading could certainly be reduced, as could the margins slightly. That would make it a more compact volume, both in looks and physically.

I was also not struck on the cartoon-style illustrations. I didn’t find them illuminating (indeed at times downright confusing) and felt that maybe a few more, better, diagrams were needed for the target audience.

One thing which Lewis does however do well is to write a summary paragraph or two at the end of each chapter. Other authors please copy.

Is this a bad book? No, certainly not. It would likely work very well for an intelligent layman. It is merely that it didn’t work for me; but then it probably wasn’t intended to.

Overall Rating: ★★★☆☆

Faecal transplants (the transfer of beneficial bacteria from the colon of one person into the colon of another) are not an entirely new idea. Their first use in Western medicine dates to 1958, but they have been a part of Chinese medicine since the 4th century. Is there anything the Chinese didn’t invent?

Faecal transplants (the transfer of beneficial bacteria from the colon of one person into the colon of another) are not an entirely new idea. Their first use in Western medicine dates to 1958, but they have been a part of Chinese medicine since the 4th century. Is there anything the Chinese didn’t invent? And that is hardly surprising when one reads of some of the major surgical interventions that were done on-site by the side of roads and in fields — and yes that does include things like open heart surgery! Which is really scary when one considers that one would not normally want to have this done even in the controlled environment of a hospital operating theatre with three or more surgeons and a full theatre team present. Whereas here this is all done by one trauma surgeon and a paramedic (albeit a super-trained one) in the field with no sterile environment.

And that is hardly surprising when one reads of some of the major surgical interventions that were done on-site by the side of roads and in fields — and yes that does include things like open heart surgery! Which is really scary when one considers that one would not normally want to have this done even in the controlled environment of a hospital operating theatre with three or more surgeons and a full theatre team present. Whereas here this is all done by one trauma surgeon and a paramedic (albeit a super-trained one) in the field with no sterile environment.

This last I do not understand; although there must be a genetic something there as my father was the same. He’d not sleep well but then be dead to the world all morning. I remember him being like this even when I was a teenager. Even on non-work days my mother would be up by about 8.30 and around 9-9.30 bring both me and my father cups of tea (in a desperate attempt to get us out of bed). I’d struggle into consciousness and descend by around 10. But not my father. He’d appear at 11, or later, with the words “It’s very odd, I found this cold cup of tea by the bed”.

This last I do not understand; although there must be a genetic something there as my father was the same. He’d not sleep well but then be dead to the world all morning. I remember him being like this even when I was a teenager. Even on non-work days my mother would be up by about 8.30 and around 9-9.30 bring both me and my father cups of tea (in a desperate attempt to get us out of bed). I’d struggle into consciousness and descend by around 10. But not my father. He’d appear at 11, or later, with the words “It’s very odd, I found this cold cup of tea by the bed”.