I the last couple of days I’ve seen two articles, of very different natures, invoking George Orwell (1903-1950, right) against the deceit and obfuscation of modern politics, and indeed public life generally.

I the last couple of days I’ve seen two articles, of very different natures, invoking George Orwell (1903-1950, right) against the deceit and obfuscation of modern politics, and indeed public life generally.

The first goes under the banner 10 George Orwell Quotes that Predicted Life in 2015 America, although it applies just as well to any other country. Here are a few of the Orwell quotes (sadly not referenced):

All the war-propaganda, all the screaming and lies and hatred, comes invariably from people who are not fighting.

War against a foreign country only happens when the moneyed classes think they are going to profit from it.

In a time of deceit, telling the truth is a revolutionary act.

Journalism is printing what someone else does not want printed: everything else is public relations.

Threats to freedom of speech, writing and action, though often trivial in isolation, are cumulative in their effect and, unless checked, lead to a general disrespect for the rights of the citizen.

I’ll wait here while you think about those for a few minutes …

…

…

…

OK? Good. Then I’ll resume …

The second article is quite a long essay in last Saturday’s Guardian from Dr Rowan Williams, former Archbishop of Canterbury. But don’t let that deter you because the article is erudite, well-written and in the tradition of English essay-writing. It is an edited version of this year’s Orwell Lecture.

[Orwell was working at what may well have been the height of the English art of essay-writing — and he was a master essayist. Essay writing was the way for journalists and intellectuals to summon up and communicate their thoughts; which is why we were taught to write essays at school. It was essentially the 1920s to 1950s version of modern blogging — at least the more serious end of blogging.]

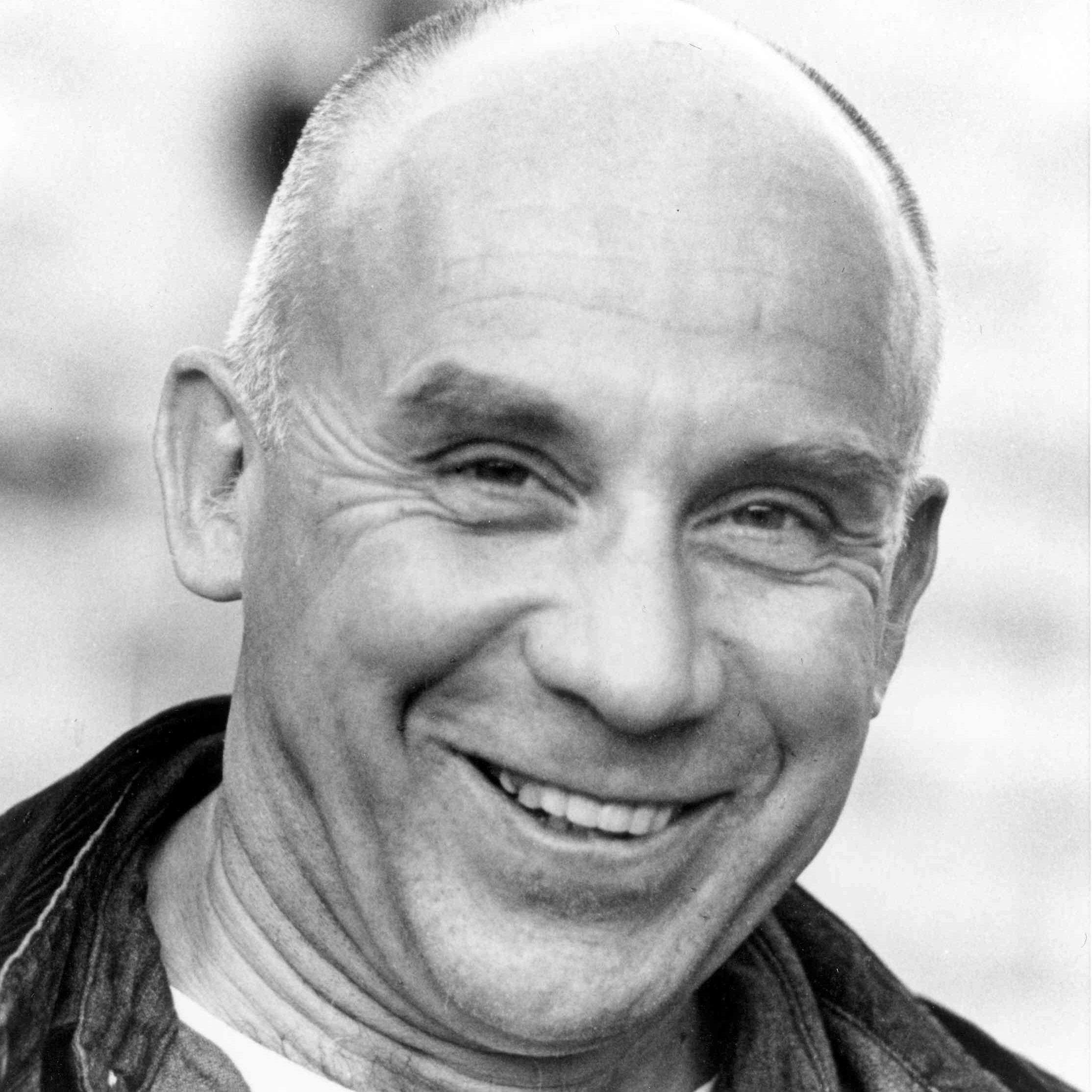

In his article Williams looks at the way in which Orwell, and his contemporary Thomas Merton (an American Roman Catholic monk, 1915-1968, pictured right), teach us about the language of terror and war. Essentially the thesis is that in order to counteract the obfuscation of “military strategists and politicians” the commentator has to write well — clearly, concisely, transparently — in order to permit communication and hence understanding.

In his article Williams looks at the way in which Orwell, and his contemporary Thomas Merton (an American Roman Catholic monk, 1915-1968, pictured right), teach us about the language of terror and war. Essentially the thesis is that in order to counteract the obfuscation of “military strategists and politicians” the commentator has to write well — clearly, concisely, transparently — in order to permit communication and hence understanding.

Williams’ essay is dense. So dense I had to read it twice. Nevertheless it is itself clear and well written — so don’t let the density put you off; it is very well worth reading. This is where I would normally give you a couple of quick quotes as the nub of the article, but were I to do that here I would have to reproduce the whole essay! That is how good it is. But undeterred, I will anyway because Williams says it so much better than I can …

Bureaucratic double-speak, tautology and ambiguous cliché not only dominate the language of public life from the health service to higher education, talking and writing badly also prepares the ground for military and terrorist action.

Merton relished the comment of an American commander in Vietnam: “In order to save the village, it became necessary to destroy it”.

When the agents of Islamist terror call suicide bombers “martyrs”, the writer’s job is to direct attention to the baby, the Muslim grandmother, the Jewish aid worker, the young architect, the Christian nurse or taxi driver whose death has been triumphantly scooped up into the glory of the killer’s self-inflicted death.

Both Merton and Orwell concentrate on a particular kind of bureaucratic redescription of reality, language that is designed to be no one’s in particular, the language of countless contemporary manifestos, mission statements and regulatory policies, the language that dominates so much of our public life, from health service to higher education. In its more malign forms, this is also the language of commercial interests defending tax evasion … or worse, governments dealing with challenges to human rights violations, or worst of all (it’s in all our minds just now) of terrorists who have mastered so effectively the art of saying nothing true or humane as part of their techniques of intimidation. In contrast, the difficulty of good writing is a difficulty meant to make the reader pause and rethink.

Our current panics about causing “offence” are, at their best and most generous, an acknowledgement of how language can encode and enact power relations … But at its worst, it is a patronising and infantilising worry about protecting individuals from challenge; the inevitable end of that road is a far worse entrenching of unquestionable power, the power of a discourse that is never open to reply … On both sides of all such debates, there can be a deep unwillingness to have things said or shown that might profoundly challenge someone’s starting assumptions.

Yes it is a dense, but good and illuminating, essay. It’s well worth the effort required to read it. And when you’ve read it, please hammer its lessons into the concrete heads of our politicians.

I the last couple of days I’ve seen two articles, of very different natures, invoking George Orwell (1903-1950, right) against the deceit and obfuscation of modern politics, and indeed public life generally.

I the last couple of days I’ve seen two articles, of very different natures, invoking George Orwell (1903-1950, right) against the deceit and obfuscation of modern politics, and indeed public life generally. In his article Williams looks at the way in which Orwell, and his contemporary Thomas Merton (an American Roman Catholic monk, 1915-1968, pictured right), teach us about the language of terror and war. Essentially the thesis is that in order to counteract the obfuscation of “military strategists and politicians” the commentator has to write well — clearly, concisely, transparently — in order to permit communication and hence understanding.

In his article Williams looks at the way in which Orwell, and his contemporary Thomas Merton (an American Roman Catholic monk, 1915-1968, pictured right), teach us about the language of terror and war. Essentially the thesis is that in order to counteract the obfuscation of “military strategists and politicians” the commentator has to write well — clearly, concisely, transparently — in order to permit communication and hence understanding. This is about how to do good science — indeed any good investigation. What Feynman is saying in the article is that in doing an investigation one has to publish the full scenarios. Whatever the outcome, why could it be wrong. If the experiment didn’t work, why might this be. And importantly, show that you understand, have accounted for, and can reproduce any prior work and assumptions on which your work depends.

This is about how to do good science — indeed any good investigation. What Feynman is saying in the article is that in doing an investigation one has to publish the full scenarios. Whatever the outcome, why could it be wrong. If the experiment didn’t work, why might this be. And importantly, show that you understand, have accounted for, and can reproduce any prior work and assumptions on which your work depends.